OK so there may be no such word as Graddage but it is so important to landscape photography, and especially with transparency film, that perhaps there should be. (“The Black Art of knowing just which grad to pick to get the best transition between maximum effect of the grad to transparent” didn’t quite have the same kick).

This topic was something I wanted to research for a while but an article over at the Singh Ray blog. Darwin Wigget does an excellent job in real world experimentation and the results are enlightening but I hope to add a little to the discussion.

So what is all the fuss about, shouldn’t we just work out how many stops we need and then pick the appropriate grad? Well you could but then you’d have to choose a hard or a soft and you’d better know how fast that transition will happen otherwise what could have been a perfect photo will have a hard dark break in it or you will still end up with burnt out skies.

So how fast does a grad transition from dark to light? This depends on the manufacturer, but with a couple of quick measurements, Lee and Singh Ray filters seem to have a transition for hard grads of about 10mm and for soft grads about 50mm.

The way this transition transfers onto film or sensor is dependant on quite a few things. The main ones I will be looking at are the distance the grad is from the lens, the focal length, the type of lens design and the aperture.

Firstly it’s probably good to mention the possible flaw in the Singh Ray article. The lens that was used for most of the test results was a 17-40mm. This lens is of a design that is peculiar to SLR wide angles. It’s called a ‘retrofocus’ lens and it’s existence is mostly to get around the problem that once you get to very wide focal lengths on an SLR, the mirror gets in the way of standard lens design (e.g. for a 17mm lens, the focal point of the lens would have to be 17mm from the sensor. Not feasible).

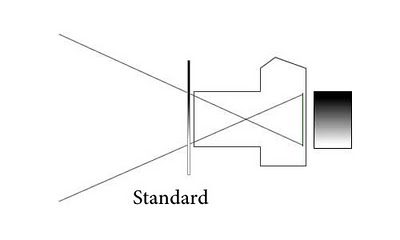

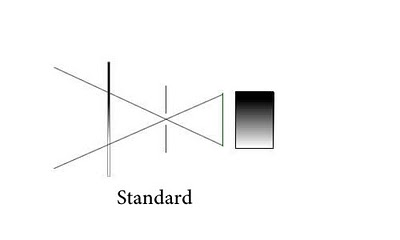

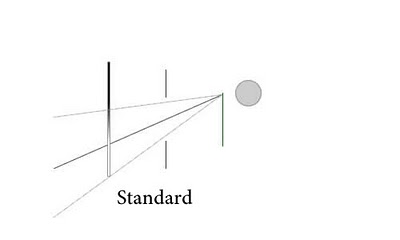

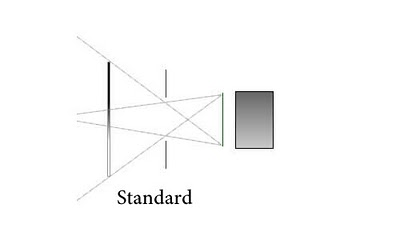

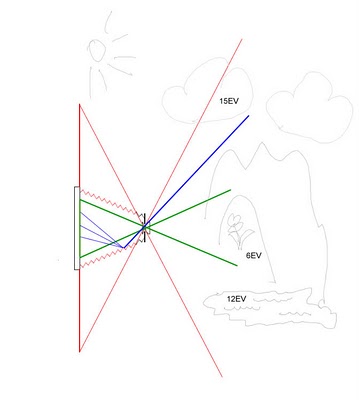

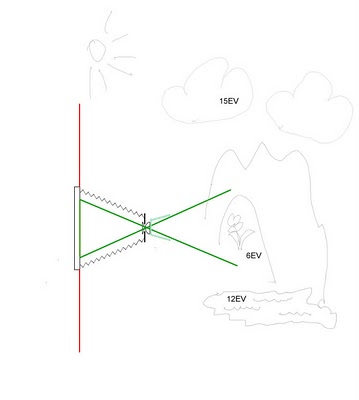

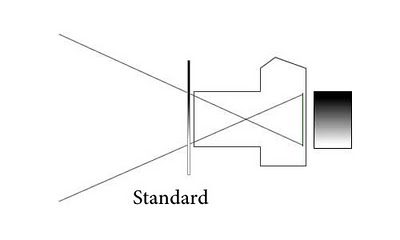

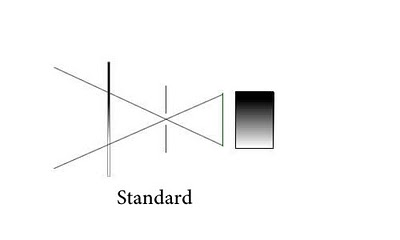

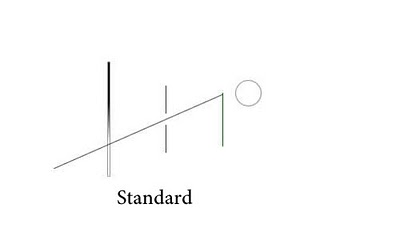

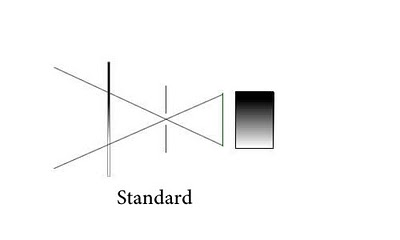

If we look at the diagram below we can see my crude effort to show how a standard lens works and how it ‘sees’ the grad.

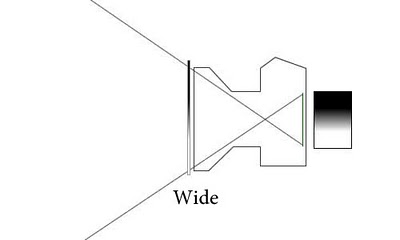

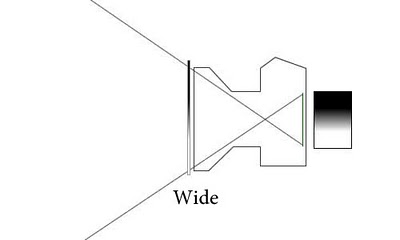

So the distance from the point where the light rays cross to the film/sensor is the focal length of the lens. Here is a wide angle design showing how the focal point is closer to the senor. Notice how on the wide angle design, the transition point is harder.

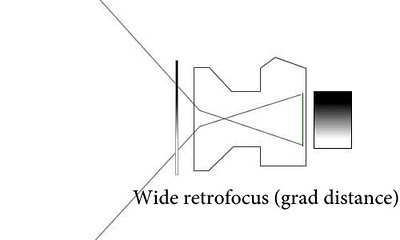

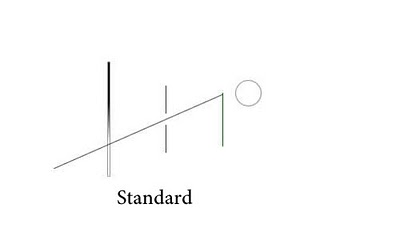

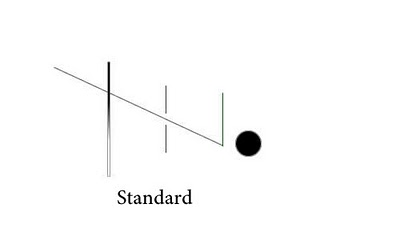

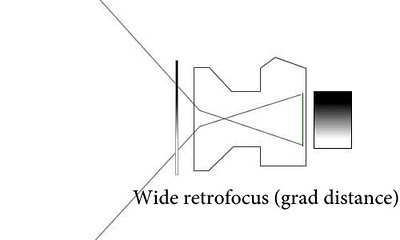

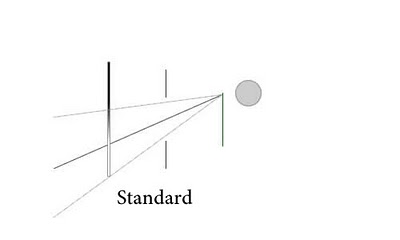

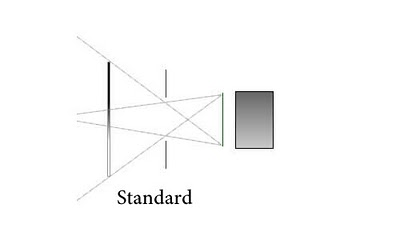

If we now look at a retrofocus design, we can see how the lens rays are moved into a more parralel path (this is also a good thing for sensors as they don’t like having light arriving at them at sharp angles, something Leica know a thing or two about).

Because the grad is so close to the ‘nodal point’ of the lens (the point where the light rays would have crossed if they hadn’t been munged by retrofocusness and other effects – shown on the picture as a green crossing point), the transition is very soft. However, moving the grad a little further away from the lens, by putting it in the last slot for instance, makes the transition harder quite quickly.

Also, retrofocus design lenses have an aperture that isn’t near the nodal point of the lens.. Before I can explain how this makes a difference I’ll try to explain why the aperture makes a difference in the first place.

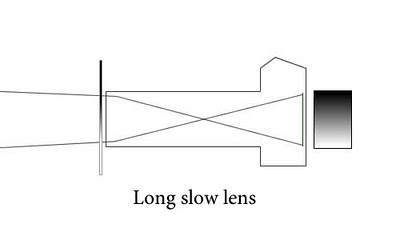

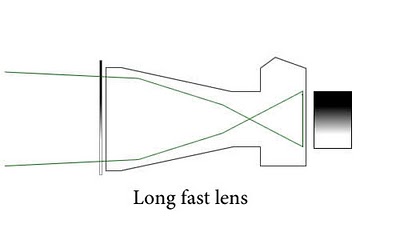

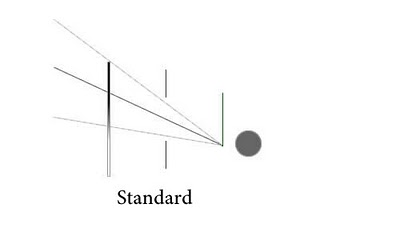

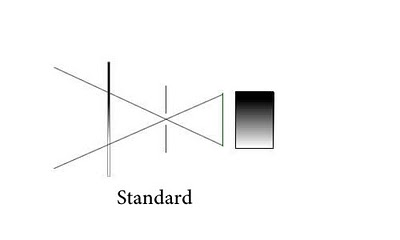

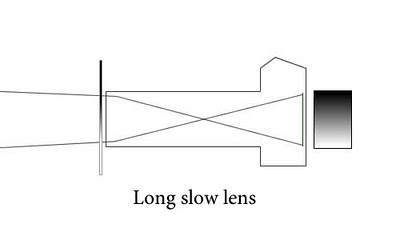

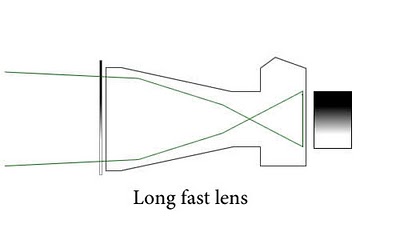

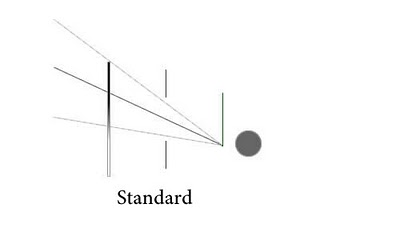

So what about long lenses? Well Here we get a little more complicated because some long lenses also play with the light paths and hence the same focal length can have differing hardnesses of transition depending on how this happens. The following two diagrams show a long lens where the first is simple and the second has some juggery pockery going on to increase the aperture.

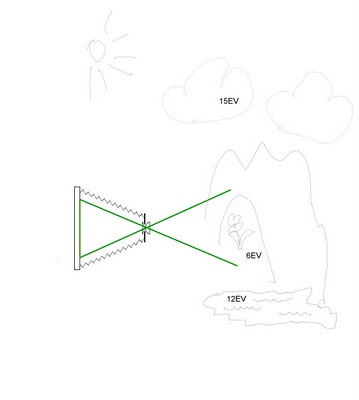

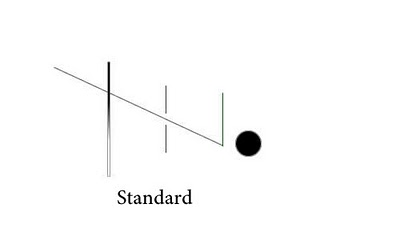

If we have a lens with a very small aperture, we can see that the grad transition is projected accurately through the lens to the sensor/film.

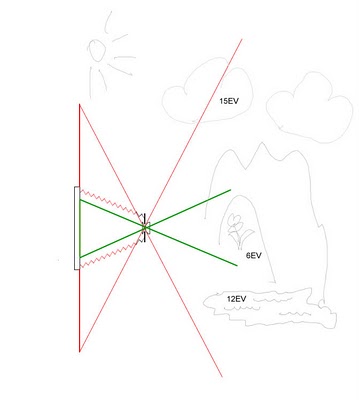

If we have a larger aperture however, the grad is effectively ‘blurred’ (after all it is out of focus). This blur changes the density at the top and bottom of the sensor/film. The following two show how the density at the top of the sensor changes.

and the following show how the density at the bottom changes

This means the gradient is a lot softer as shown below

The amount of blur is dependant on the width of the aperture (which is focal length / fstop). I’ll expand on this a little at the end.

The aperture in a retrofocus lens isn’t in the same position as a normal lens and doesn’t have the same effect on hardness as on a normal lens. Now I can’t work out how much effect it should have because the lenses are particularly complicated and it may be that I’m wrong in how this affects the transition but it would make sense to use a standard design as well as the retrofocus design in order to provide a balanced result (perhaps someone can contribute?). In reality, it’s good to know that the aperture doesn’t have as large effect on the 17-40 as it’s a very common landscape lens.

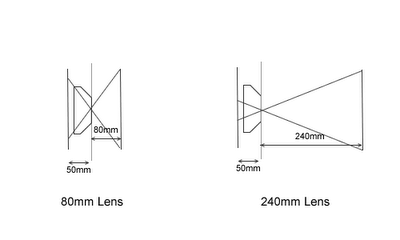

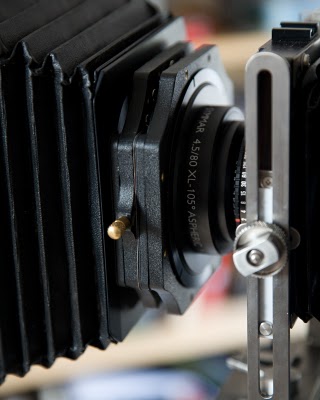

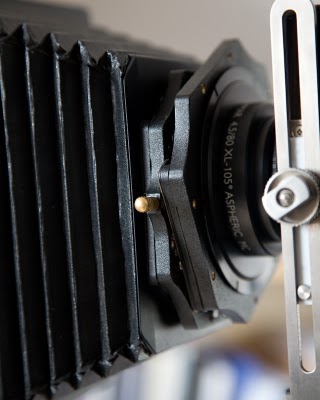

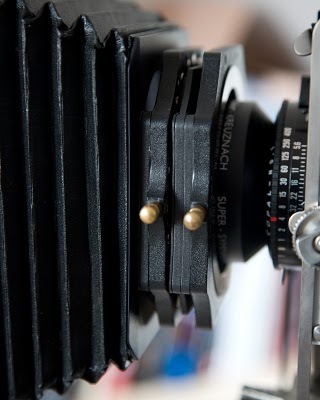

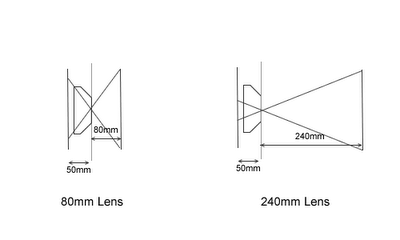

For large format photographers, we’re in less complicated territory. The following diagram shows a couple of lenses that I own and I hope to show how the transition hardness is affected across the other lenses I own.

The distance between the lens board and the grad plays a big part in the hardness of the transition as the length of the transition on film is equal to the length on the grad divided by the distance from lens board to grad and multiplied by the focal length. The following table shows this calculation for all of the lenses I own.

All measurements are in millimeters. The transition length is the distance it takes to go from transparent to full density on the film surface. The percentage is the proportion of the film that the transition zone covers (presuming portrait orientation 5×4 film).

You can easily see that on the 80mm, a transition percetage of 13% makes for a hard grad, wheras on the 240mm, the transition zone is 55% of the frame, no good for hard horizon sunsets then.

With soft grads, the 240mm is almost useless.. A 3 stop soft grad would only get the chance to get 2 stops of transition in. On the 80mm, the soft grad has the full transition across 70% of the frame.

This makes Joe Cornishes full range of custom ‘Extra Hard’ grads understandable. I imagine he knows from experience how fast a grad transitions depending on what lens he is using. After doing these calculations I know realise I’ve got a big Lee filter bill coming too

My next job is to work out just how much the aperture affects the transition on my large format lenses.. My gut feeling says that at f22+ it won’t have much effect but I’d like to know how much you need to stop down to get a representative effect (to make focussing easier for instance).

I hope with your new found Graddage skills that the right grad is now a little less of a hit or miss affair.

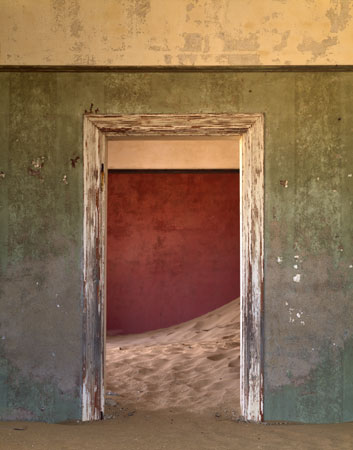

I started the post with picture I took on the way back from my Gower Light and Land trip. I’d stopped at a layby right in the middle of Wales (near Welshpool) and this was the view I was presented with when I walked to the bottom of the car park. I put this image up because it ended up very dark across the top of the land. I’d used a 2 stop hard grad and wanted to stop back the sky but not the land. The picture you see had to be worked on quite a bit to get things back and orderly. I now know that with my 240mm lens, I really need an extra hard grad to accomplish the effect I wanted and the reason that the land was so dark is that it was underexposed by a stop or two because the transition zone overlapped the land by about a third.. I’ll post the original picture up when I get chance.

Click to view full post including 2 Comments